Pushing the Boundaries

In the first part of this series, I wanted to lay the groundwork for a discussion of narrative in video games. Before we move on to a more technical discussion, I thought it would be helpful to look at some recent games that have pushed the envelope of interactive narratives.

Ready?

Night in the Woods

It seems like the first thing that hooks a player to this game is the unique art style and music, which are both exemplary. But the element that keeps you playing is the writing — clever, witty and believable, the writing draws characters that are as unique as the art style, and puts them in a story that is both down to Earth and unexpected.

Night in the Woods starts with the main character returning to her hometown. As you explore, she strikes up conversations with family, friends, old acquaintances and even some strangers. Most of the outcomes from those interactions are minor, but there is one overarching thread: who is your best friend? The game tracks who you spend the most time with by asking several times who you want to hang out with — and the character you spend the most time with affects how the conclusion unfolds.

Another interesting point to note about this mechanic is the careful balance between hiding the ultimate outcome of this decision while still making it clear that it is a choice holding weight. For example, as soon as you start the day, you are primed with the choice you will have to make later:

Eventually, you are prompted for your decision. Each friend outlines what will happen if you choose to spend time with them — and what you’ll be missing out on if you don’t choose them:

While this framing makes it clear that you’re making a significant decision, there are no immediate ramifications — except, of course, for allowing you to spend more time with that friend. In fact, later that evening, you return to your laptop to see that the friend you didn’t hang out with holds no ill-will against you, and even lets you know what they were up to. It’s not until the end of the game that you see how your choices impact the story.

80 Days

80 Days is arguably the best example of a narrative game available today. It is made by Inkle, who not only has another engrossing narrative game called Sorcery!, but has also released their story-building toolkit as open source. They’re serious about the genre, and it shows.

I single out 80 Days for several reasons: it’s replayable, it’s engrossing, and every choice has meaning.

Replayable because the path you take around the world is entirely up to you. That’s the “game” portion of this narrative game — you are given a globe dotted with cities, and you have to find your way from one city to the next, with the ultimate goal of making it completely around the world. Your first trip may take you through Europe and India, whereas your second trip may instead go north through Scandinavia and Russia. While some journeys may repeat destinations, the majority of each playthrough will be unique — and even when it does repeat, there are enough choices embedded along the way that you can still have a completely new experience.

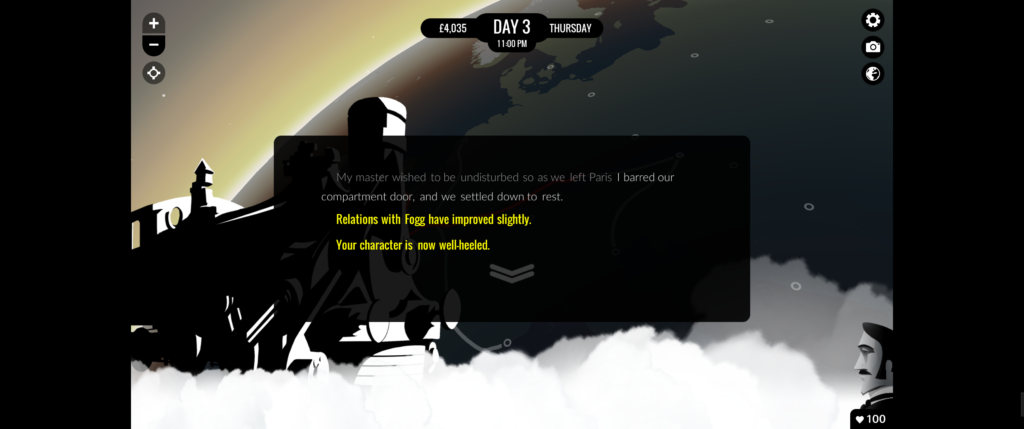

Engrossing because the quality of writing is stellar. You take on the role of Passepartout, the manservant to one Phileas Fogg of London, who recently placed a wager that he could circumnavigate the globe in 80 days. It is your job to not only keep your master happy and comfortable, but also find the fastest route around the world without going bankrupt. Every city comes alive with its own atmosphere and culture. The people you talk to add realism and context as they express their wonder or fear. Halfway through a journey, I will often find myself simultaneously rushing to meet the 80 day deadline while also wanting the game to continue so that I can learn more about the city, country and world that the story presents.

Every choice has meaning because the prompts you are given throughout the narrative have immediate feedback — whether it’s as minor as losing a few pounds to a pickpocket or as major as being thrown in jail. The game also remembers key characters that you’ve met, or important knowledge that you’ve gained, so that you can leverage certain advantages later in the story. While some parts of the story are repetitive, the game uses some smart randomization and insight into previous playthroughs to make each game slightly more interesting than the last.

All that said, the game isn’t perfect. There is an inventory mechanic in the game that ostensibly lets you take advantage of global supply and demand to turn a profit and keep your journey going without dipping into savings. However, its implementation is clunky and shoved off to the side in a way that makes it difficult to fully leverage. As a new player, it can be especially difficult to keep track of which items can be sold in what locations for a tidy profit — or, more to the point, how to get to those locations.

You will also occasionally be told that your relationship is getting stronger or weaker with your master. It’s unclear what this means or how it affects the game — and perhaps that is intentional. But if you take the effort to tell the player this information, the player expects to see some impact from that information in the game.

But overall, these are minor quibbles — this is an experience that sits at the pinnacle of narrative-based games.

Life is Strange

While most “choose your own adventure” stories lock you into whatever choice you make, Life is Strange asks, “what if you could change your mind?”

Life is Strange follows the character of Max as she starts school. Over the course of several chapters, she meets new characters as well as refamiliarizing herself with characters from her past. But in the course of doing so, she also discovers a strange power: the ability to rewind time. For every choice that she makes, she has the ability to go back and make a different choice.

Thinking about the story in a game such as this, the ability to rewind time forces the writer to make sure every choice has a noticeable and tangible impact. Life is Strange delivers on that requirement, although it does take an interesting approach on several key parts of the narrative. Certain choices are given a high importance — i.e., they branch the plot in some significant way — but the immediate impact of those choices have no obvious “good” or “bad” outcome. Instead, they have a mixture of both, forcing the player to decide which blend of “good” and “bad” adds up to an outcome they are happy with. And, while all of the choices in the game have a point where you can no longer rewind, these key plot beats have a hard stop that is clearly called out to the player, making it impossible to know what the long term effect of a choice is.

Ultimately, the game becomes an exploration of what choice means — how it affects our lives, and how it affects those around us. For a developer of a game with an interactive narrative, this mindset is important to consider, even if rewinding time isn’t a gameplay mechanic — because a player can still “rewind time” through save files or starting a new game.

Something else to consider: what does it mean to give certain choices more weight when presented to the player? In our day to day lives, we are never given an opportunity to see which choices will affect our lives so prominently — so why should it presented that way in a game? Does it make sense, especially for a game that has a rollback mechanic? Life is Strange cuts to the heart of many interactive narratives, and is important to play for that reason alone.

The Elder Scrolls: Skyrim

Skyrim is actually here as a counter-example. While I love this game from an exploration standpoint, it is lacking deeply in narrative. There are certainly opportunities for interaction and even choice — but most of them are shallow, causing no long term effects to you, other characters or the world. Worst of all, various incidental characters will repeat dialogue, often with the same voice actor.

This disconnect between potential and reality is unfortunate — but it is also inspiring. Here we have a game that is dripping with history and character, just waiting to be tapped. What if the world of Skyrim had an intricate narrative that matched its grand scope?

Up Next

With this context in mind, the next part will explore some ideas for adding another dimension to interactive narratives, and how they might be implemented.